But lately I have been noticing something. We don't know how to grieve here. We like to "send our condolences to the family of the deceased," but just as quickly we say meaningless things like "I just try not to think about it" or "he wouldn't want us to be sad." And that's not the worst.

The real vacuum of grief can be seen after the more subtle tragedies. When is the last time you saw candles lit in the street for someone whose spouse cheated on them? When have you seen a vigil for those that are missing their home country? When have you seen a special service held at a house of worship for all those that lost jobs in a corporate restructure? What about a wake for the family who lost a son to mental illness? Where does a teen go to recover from yet another "stop and frisk" incident which if not handled well could have been life threatening?

We have no words for these things here? "Bereavement leave" doesn't apply to these things. Instead we get angry and march and sue and fight. There certainly is a place for anger and action, but nothing can suffice for the healing silence of grieving in a safe space.

Contrary to the tough stereo-type, New Yorkers are hurting. Did you know we have more suicides here than homicides? The numbers shocked me.* We never talk about suicide here. I am a Social Worker at an organization run by Social Workers, but even we don't talk about suicide. Its as if New Yorkers are not afraid of anything except prolonged grief. We quickly cover things, and so there is a crusty attitude that forms in our heart over all that mess.

And I get it. Much of the cover up is necessary for survival. If you listen to the stories, you quickly understand. It is actually a form of white privilege for me to sit here and suggest that people stop and grieve. Who has that kind of margin? When you are working and going to school while raising three kids as a single parent, you don't have time to grieve. If the tears start flowing, will they ever stop? If you are in the shelter, undocumented, work below minimum wage and still send a third of your salary back to your home country because you are the "rich family member that made it to America," how will you have time to stop and grieve? Reality bites, and there is no time to stop and heal the wound.

We are also intoxicated with optimism. To grieve, is to question the optimism that keeps us going.

People come to NYC to make it big. In my own way, I suppose I did too. We are so convinced that we will "make it" if we try a little harder. We love phrases like "believe in yourself" and "just stay away from the haters." In churches, this thinking is sometimes called faith. The image is reinforced as we daily walk past, $20 Million penthouses in Tiribeca or $300 hand bags on 5th Ave. The images of "success" are all around us. As much as we hate Trump, he is a true New Yorker in so many ways -- addicted to the image of success.

I have no solutions here. I am just wanting to help break the silence, the silence we cover with noise. Somehow, we have got to create spaces to grieve.

Maybe we could start with the immigrant experience. No matter how much we love our lives here, don't we all feel the loss of the places we left? Don't we all believe that NYC is not quite what we hoped it would be? Are these not almost universal losses carried by all New Yorkers? Could we acknowledge that at least?

Could faith communities be the space for this? Tragically, many use religion to avoid grief. The faith rhetoric is a thinly veiled version of the American dream. "Just believe it and you can do it." That is not the model I see in our Creator who came to die. If He wept and died and calls us to die, wouldn't that mean at least that we are not afraid of the same feelings. Maybe the promise of His resurrection could give us courage to go deep into the realities of our losses and the losses of those around us.

I think it could. The caver with the strongest rope can descend into the lowest crevices. Religion if it means anything, I think it is that it is okay to grieve. "Blessed are they that mourn," Jesus said. I think this is true even if all we have to spare is a New York minute.

Who knows? Maybe it would take the edge off that crusty New York attitude as well.

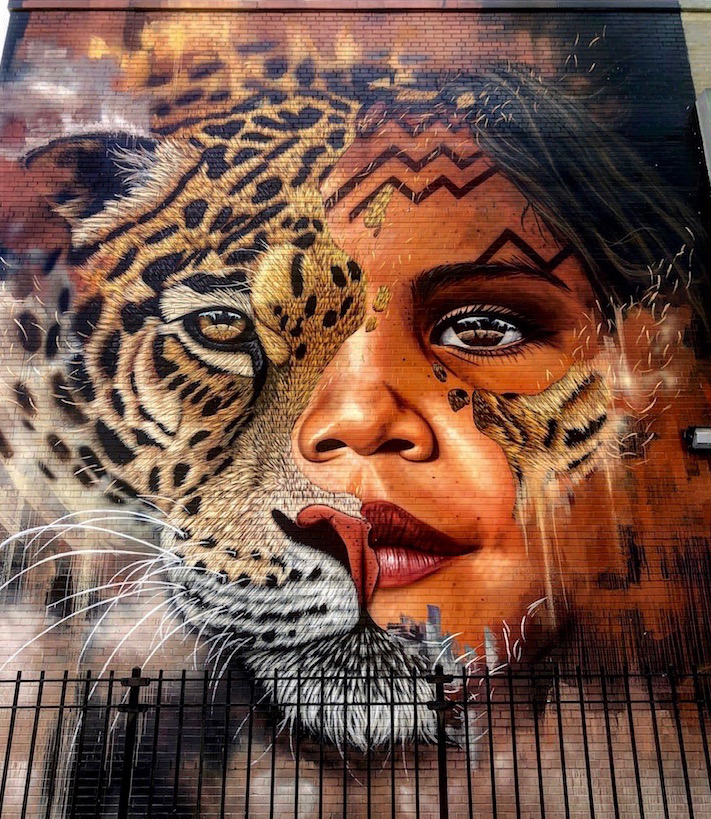

I included a few graffiti murals here because they show more than words can.

The promise of Easter is that we can be kids like this, crying/smiling in the rain.

* https://www.villagevoice.com/2016/09/15/report-suicides-surpass-homicides-in-nyc/